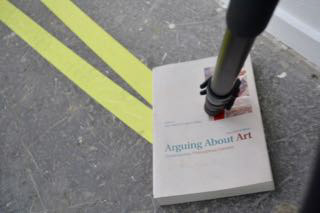

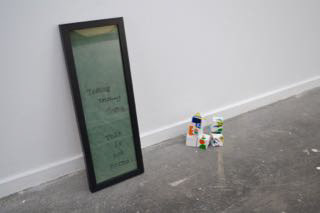

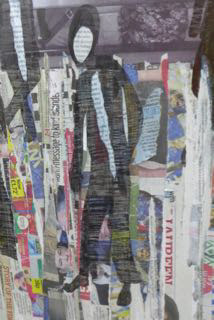

VOLTS:: Echoes of Exclusion was an exhibition hosted in Spike Island's Test Space created by volunteers from the Spike Island community drawing inspiration from the philosophical nature of Test Space, in particular the sensations of transience and dissociation that pervade the space. Contributing artists include Shirley Alderton, Caroline Blake, Aloys Feeney, James Norman, Annie O'Connor, Sarah Ramsey, Cat Smith and Beckie Upton.

Aloys was involved in the organisation and curation of the exhibition, coordinating applications and artist statements from exhibitors and helping with exhibition design. He also participated in the exhibition as an artist by contributing a text piece entitled 'Outright Barbarous' which can be read below.

More information can be found here.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

Image credit: James Norman.

‘Outright Barbarous’

Understanding the Exclusory Nature of Speech in The Art World

The vernacular of those ordained in the art world challenges and mystifies the beholder, exuding a sense of bemusement, perplexity or even chagrin. To overcome bewilderment viewers are forced to exhume meaning from unparsimonious structures, immersing themselves in the territory of the unknown. This polyonymous system exists to debar the constructed inerudite masses from integrated and assimilated engagement, reinforcing obsolescent archetypal notions of social structure. The supporters and upholders of this doctrine vindicate its eminence as an inevitable rational consensus facilitated by the imperative of coordination as a desideratum.

The language of art exhibitions has been carefully crafted to exclude viewers who are not familiar and force those who wish to engage and understand the art world to become familiar. ‘Art Speak’, ‘International Art English’ or simply jargon; is a tool designed by those who wish to keep art understanding in the possession of an educated elite. This exclusive nature reinforces out dated, top-down, models of art and culture in society. Those who use Artspeak often defend its existence as a natural answer to the need for a unifying language between curators, critics, practitioners and educated audiences.

In George Orwell’s 1946 essay Politics and the English Language, the author laid out six elementary rules for clear and concise prose:

(i.) Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

(ii.) Never use a long word where a short one will do.

(iii.) If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

(iv.) Never use the passive where you can use the active.

(v.) Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

(vi.) Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

Orwell believed that language, more specifically our choice of words, could be used to manipulate society and influence thought. Ultimately he argued that bad writing comes from corrupt thought and often is used to justify unjust or immoral acts. One might wonder what Orwell would make of the contemporary art world and those who use ‘International Art English’ to deliberately exclude specific audiences.

If cultural institutions wish to make good on their claims to become more inclusive and representative of society as a whole they need to adopt a linguistic style that doesn’t require a prerequisite understanding of the art world to decipher.